The Natural Eye Bursary 2021

The Natural Eye Bursary is awarded by the SWLA annually to support independent art projects that focus on wildlife as a subject. The work on display here is a selection of work in progress from this year’s three bursary winners’ projects, due for completion in 2022.

All three of this year’s bursary winners demonstrate a determination to use their creativity to explore and research a particular theme. Interestingly, each of these individual enquiries into wildlife is carried out on very different scales. Adrien Brun’s mission for example, to discover Norway’s vast and seemingly untouched backcountry immerses him in nature on the epic landscape scale. On his expeditions Adrien searches for wildlife and with it an experience that might connect him to his ultimate goal of finding wilderness.

Working at the opposite end of the macro spectrum from Adrien, Ibby Lanfear’s project hones in on an individual species at a far more intimate scale. Her project is a long term study focused on a single family of barn owls and an experiment to document their annual life cycle through the minute dissection of their regurgitated pellets.

Georgina Coburn, on the other hand, has been compelled to explore the richness of ecosystems and variety of species and habitats within walking distance of her own home. Crucially, these pockets of urban nature have become a source of resilience for her and her local community during the global pandemic. As Georgina puts it:

‘Many people discovered the hope and resilience to be found watching animals, birds and the changing seasons, not as a pastime, but an imperative. … I want to capture the wonder of individual species and the sense of connection we feel when we encounter them, making small things visible as part of a whole ecosystem.’

As Georgina describes, connection, either with nature, by expressing an experience of wildlife, or the interconnectivity of the natural world itself, is an idea that again features with importance in all three of this year’s bursary projects. Whether it’s Ibby’s holistic approach to documenting wildlife’s connection to a place, Adrien’s search for a sense of wilderness or Georgina’s determination to delve into the web of life on her doorstep, all three artists are concerned in their own unique experience of the natural world. This sense of independent enquiry, observation and curiosity is leading to three very individual and original documentations of wildlife through art, which is exactly what The Natural Eye Bursary aims to encourage.

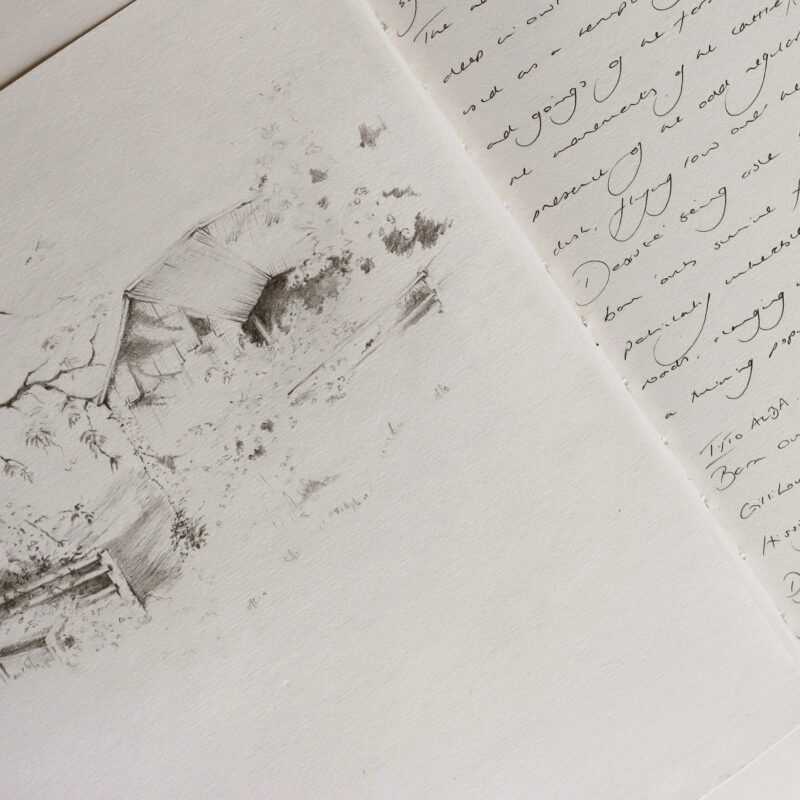

Adrien Brun: Wild, Close, Unknown

As my project has evolved, I have found a line of enquiry I can address through my art shaped around the question, what do we call ‘wild’ and why do we need it?

In Norway, wilderness is always close-by and popular as a place to exercise, but its nature and wildlife is so often overlooked. My Natural Eye Bursary project explores the wildest places around me in order to build up my first exhibition to be shown in the local hiking cabins. This is where I hope my work will leave an impression on different audiences, all using the cabins and accessing the outdoors for a whole range of varied reasons.

So far, I have made three, five-day long expeditions, which have already been productive for making observations, sketches and watercolours. I walk long distances, carrying everything I need with me, so have optimised my materials, to keep my pack below 30 kg. Each expedition I take, challenges my painting skills, dares me to tackle more complex subjects and light…a never ending story!

After my first expeditions, something quickly struck me, and the purpose of my project suddenly deepened. So far I have been in areas vast and wild as far as the eye can see. Places that I have paced up and down in every direction looking for wildlife, to eventually find…almost nothing, often to my surprise and disappointment. The more I look, the more it feels mostly empty and yet it looks so wild. Now my project is compelling me to ask what do we mean by ‘wild’ when all the predators are thoroughly exterminated, when reindeer, moose and deer populations are intensely controlled by hunting, when sheep are grazing everywhere with fences kilometres long.

My expeditions take me to the most remote places, with the least human influences, meaning maximum wildlife. But I am now facing the fact that even here, I cannot escape the realisation that wilderness is very much a relative concept. As my project has evolved, I have found a line of enquiry I can address through my art shaped around the question, what do we call ‘wild’ and why do we need it?

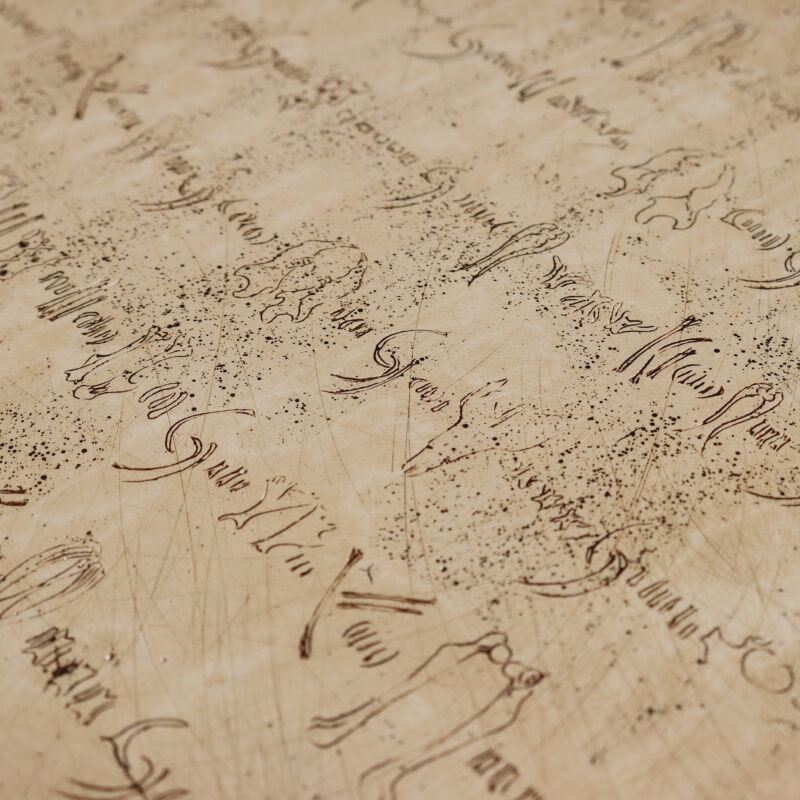

Ibby Lanfear: Owl: working towards a script of sorts.

I’ve spent the summer collecting materials from which to make pigments; experimenting with different woods for charcoal; testing the colours of the earths from the hay meadows, pastures and woods.

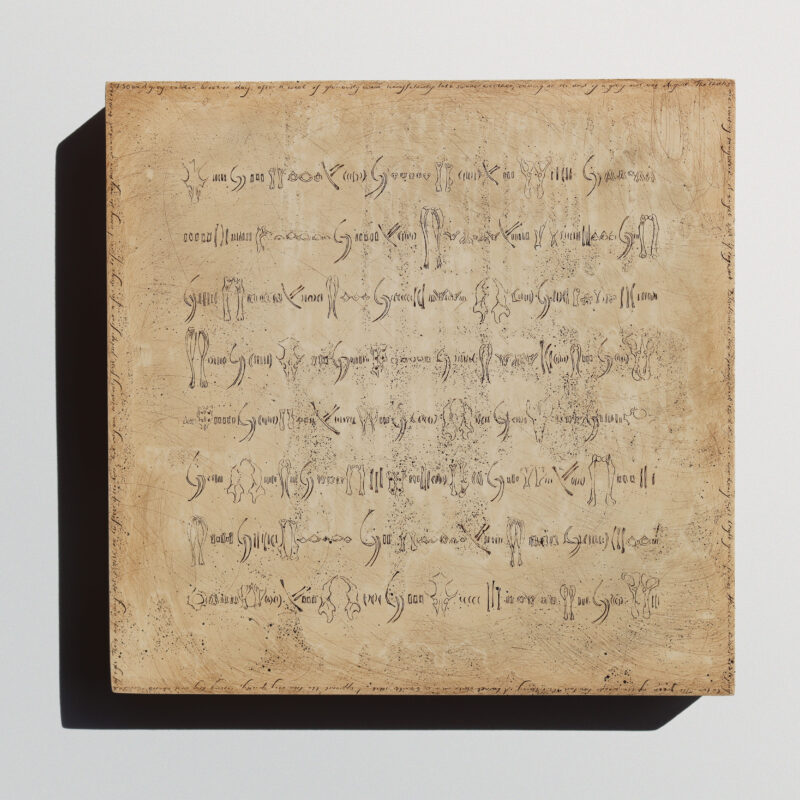

The project will tell a story of land and life through the individual pellets of a barn owl resident on a local organic farm. It involves collecting a pellet a month for twelve months, dissecting them and drawing the contents on a series of twelve gesso primed oak panels, which will constitute the final piece. In format the work will recall the medieval painting cycles The Labours of the Months. An owl calendar.

The pigments used are time and site specific, earth from the land over which the owl hunts, charcoal made from the twigs of the trees. It is hoped that while the drawings of the bones will function as an accurate record of the owl’s diet, the hieroglyphic nature of the depictions will also evoke notions of storytelling and early written language, encouraging discussion of the interconnectedness of all life, through time, and our collective dependence on the environment in which we live. The practice of drawing itself will become a means of knowing, recording and understanding.

I’ve spent the summer collecting materials from which to make pigments; experimenting with different woods for charcoal; testing the colours of the earths from the hay meadows, pastures and woods. And back in the studio, trying different oils, making paint, working out how to incorporate the fur and seeds from the pellets into the gesso. Carving, scratching. Trying to find the rhythm of a written page. Distilling a script from a language of bones. This is the first test panel. There is a way to go. All materials were collected on a cool, breezy day at the end of August.

Test panel: 585 bones. Roughly three wood mice, one shrew. Pigments (this month, earth collected from a deer track in the owl wood; charcoal from field maple, hazel, hawthorn and holly) in walnut oil on gesso and oak.

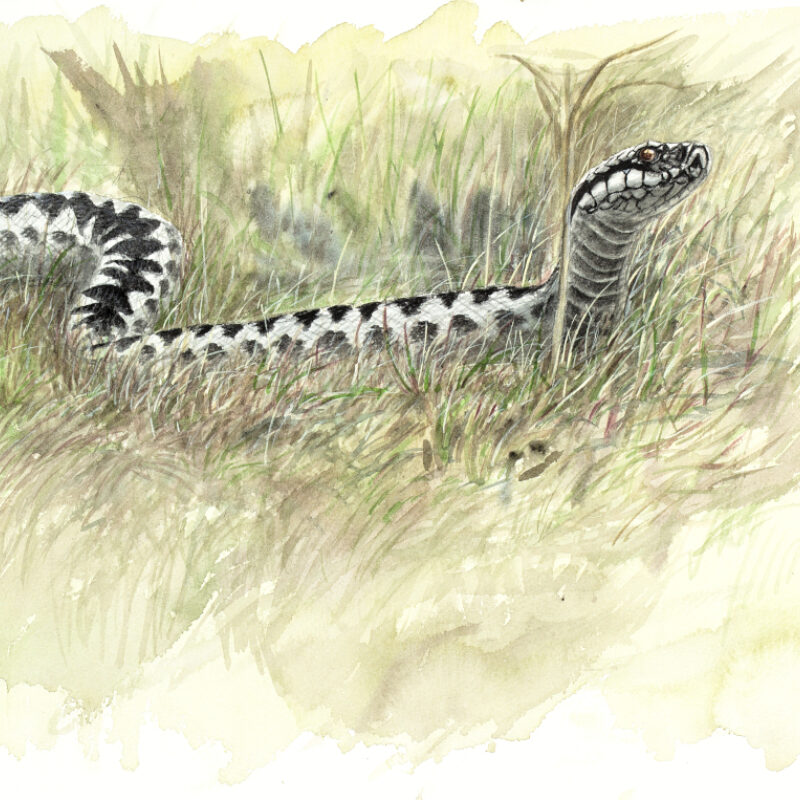

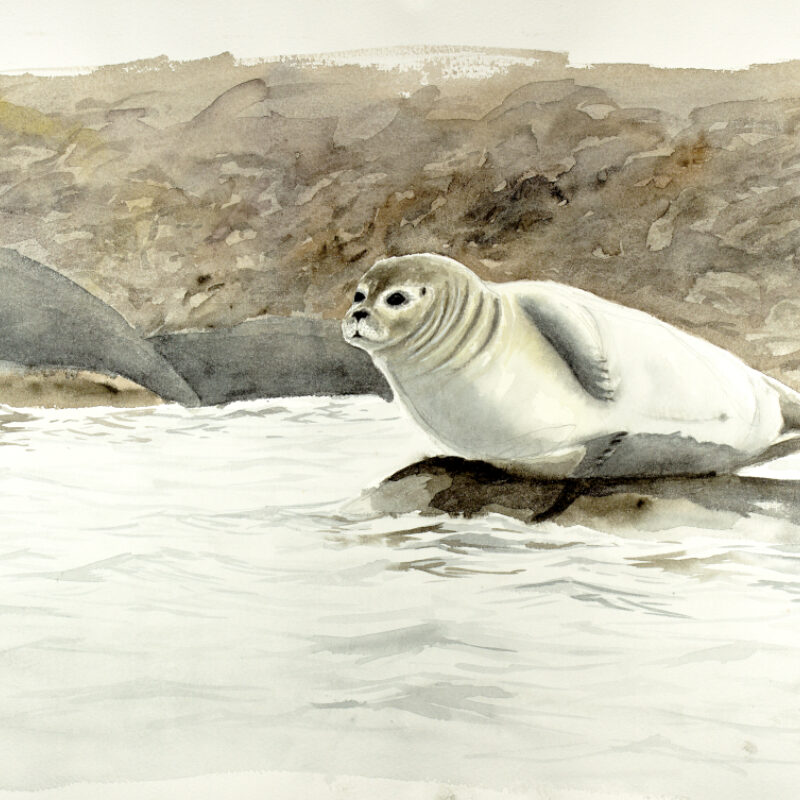

Georgina Coburn: Ness Wildlife in Lockdown

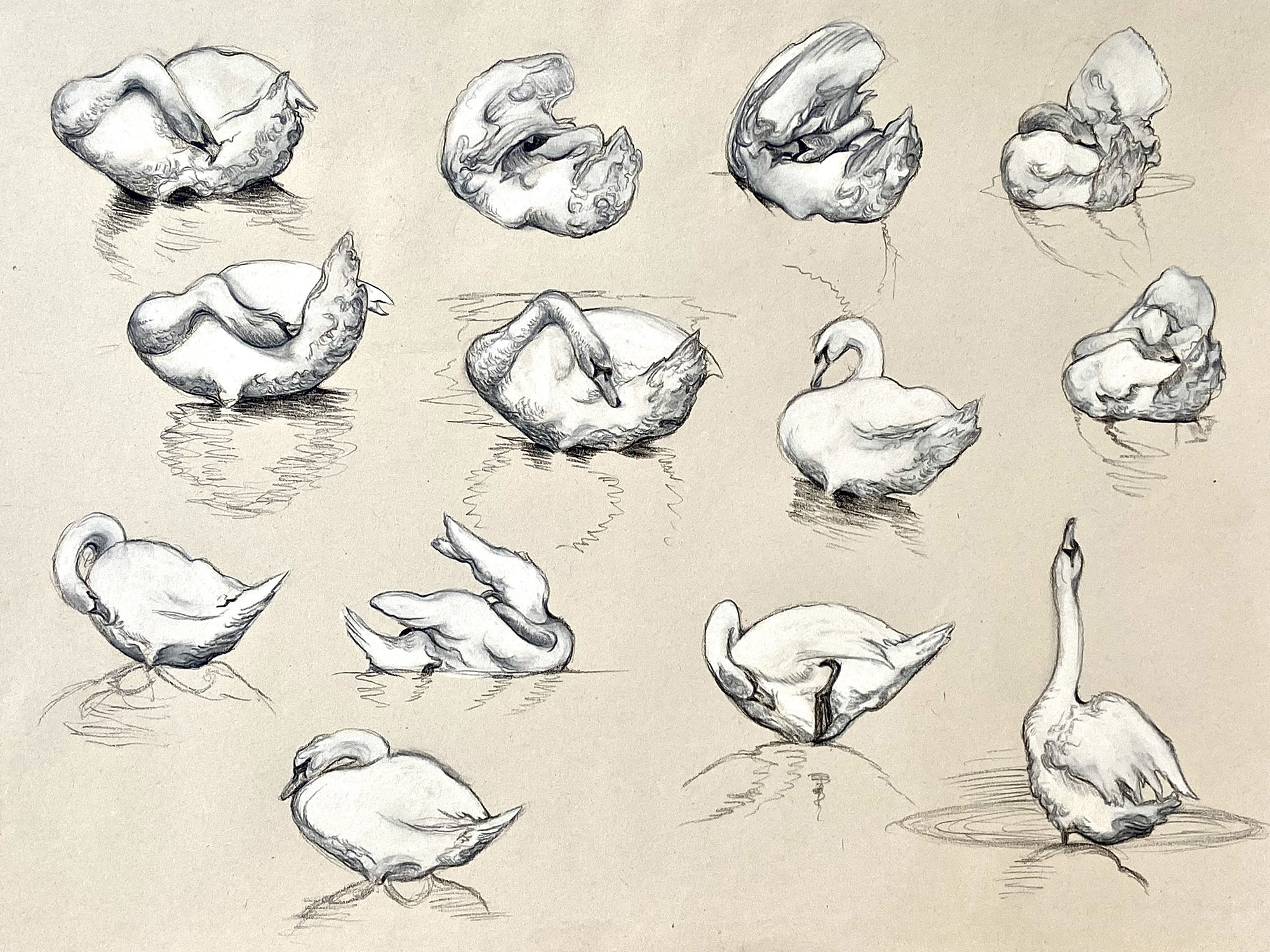

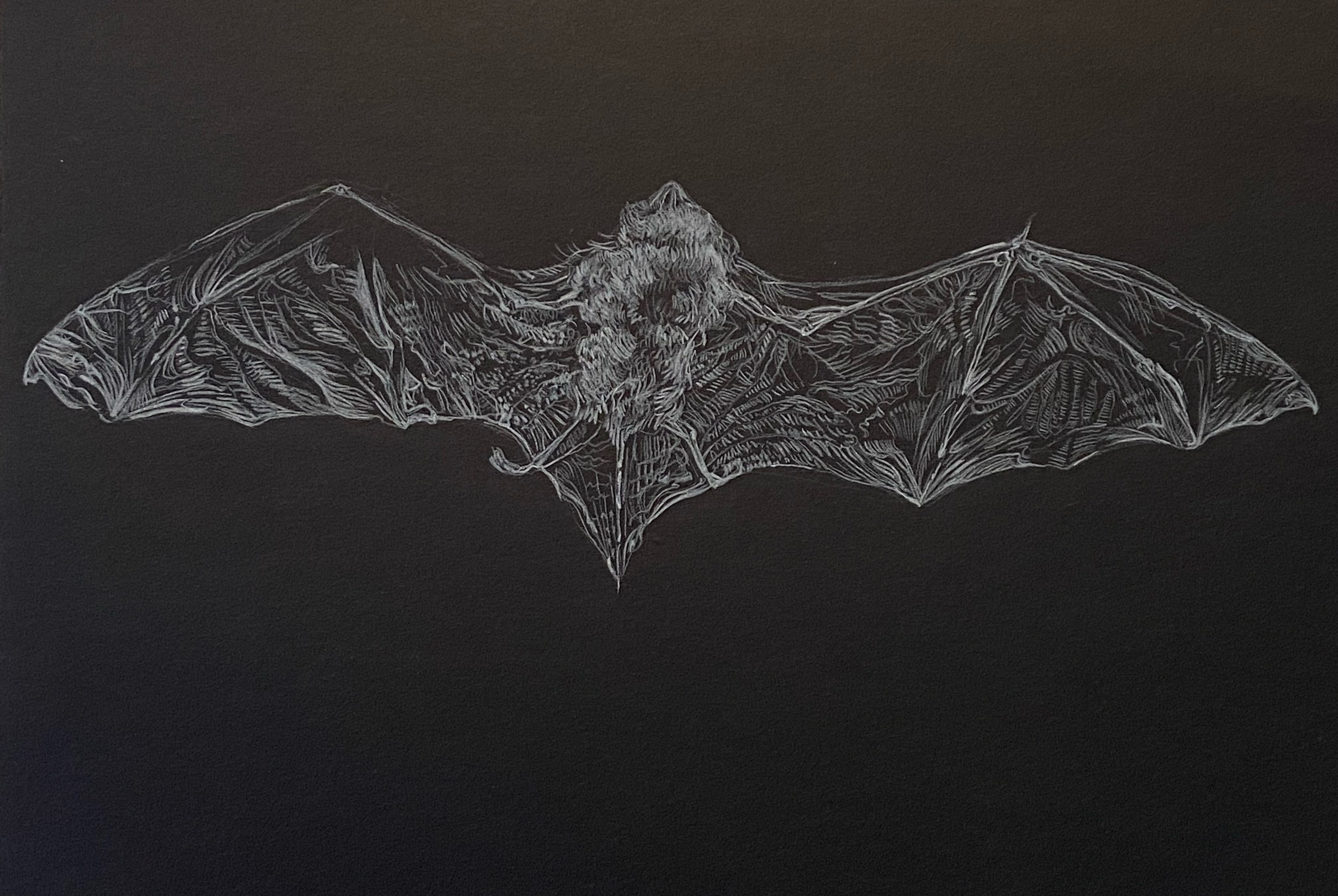

My Natural Eye Bursary project is to expand my practice by learning a new technique of stone lithography at Highland Print Studio, explore the range of mark making possibilities and produce a series of drawings and prints

The starting point for my Natural Eye Bursary project was the experience of lockdown. During daily walks along the River Ness, Merkinch Nature Reserve and Caledonian Canal, I became much more aware of the birds, mammals, fish and insects found on my doorstep. As in so many urban environments around the world, when human activity ceased, nature was able to re-establish itself; in uncut verges, parks, pavements, rooftops, balconies, canals and riverbanks. The diversity of life in these spaces is remarkable if we if we only stop to look.

For many people, the enforced pause of lockdown prompted closer examination of our essential relationship with nature. The global pandemic has shown us how fragile life is, and how nature can bounce back when intensive human activity is reduced. Many people discovered the hope and resilience to be found watching animals, birds and the changing seasons, not as a pastime, but an imperative.

My Natural Eye Bursary project is to expand my practice by learning a new technique of stone lithography at Highland Print Studio, explore the range of mark making possibilities and produce a series of drawings and prints. I want to capture the wonder of individual species and the sense of connection we feel when we encounter them, making small things visible as part of a whole ecosystem.

To date I have completed a series of sketches and larger drawings in pencil, watercolour, inks and conté, researched local wildlife, the history of stone lithography and the 155-million-year-old Bavarian limestone which is the ground for this technique. I have begun one to one tuition at Highland Print Studio and worked on a series of test stones, building knowledge of the process with each one. Lithographic stone is a beautiful surface unlike any other to draw on, carrying the history of the earth within it.

Full reports of the artist’s completed bursary projects will be published on the SWLA website later next year. Find out more about the SWLA bursary scheme on our Bursaries pages, including The Natural Eye and Seabird Drawing Course awards.