Sir Peter Scott 1909–1989

SWLA Founder Member and Past President

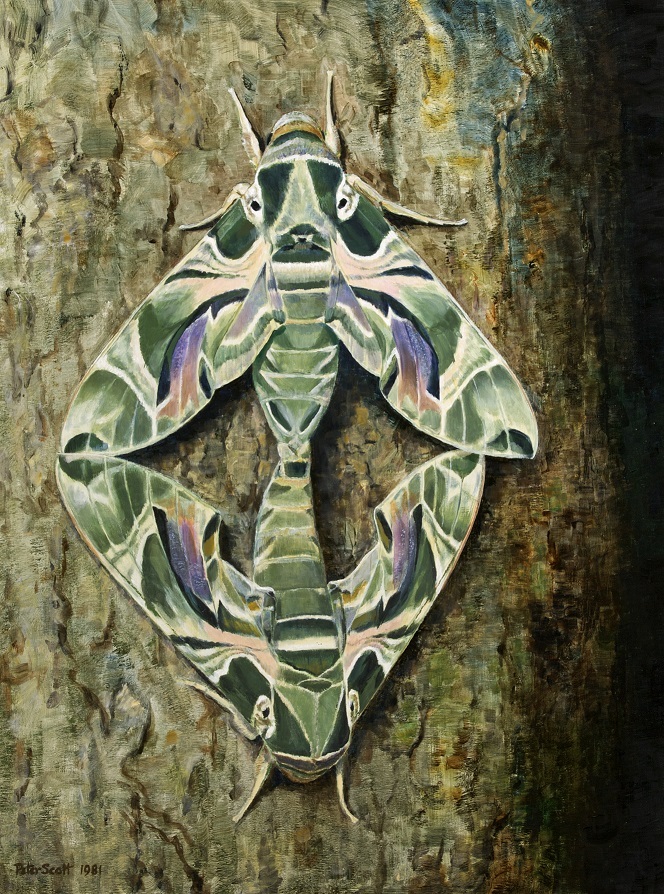

Peter Markham Scott was a painter by profession but he was perhaps best known as a television broadcaster, a leading conservationist and the founder of the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust. As a painter, he is best known for his oil paintings of wildfowl, which are now held in collections worldwide. He also drew and painted other wildlife, and his media included pen and ink, scraperboard, watercolour and gouache as well as oil. In later life he kept travel diaries, large plain paper notebooks, so that after a day in the field, he could make notes and paint watercolours of animals he had seen.

He was the only son of Captain Robert Falcon Scott, the Antarctic explorer who died on his way back from the South Pole in March 1912. As he lay dying in his tent, Captain Scott wrote a last letter to his wife saying ‘Make the boy interested in natural history if you can.’ Peter’s mother, Kathleen, fulfilled this wish ingeniously and effectively. She brought him up to be interested in and curious about nature and the environment and introduced him to people who could help with this. Being a respected sculptor, she encouraged him to draw from a young age. He learnt to look at things carefully with the result that he developed a more or less photographic memory. After seeing an animal during the day, he could sit down later and draw it accurately.

After a degree in History of Art and Architecture at Cambridge, he went on to study art at Munich State Academy and then the Royal Academy Schools, and subsequently began painting in earnest. Having become keen on coastal marshes as a result of wildfowling during his student days, his subjects were the wild birds that he had come to know and love. His first exhibitions were very successful and throughout his life he had regular exhibitions at Ackermanns gallery in London.

During World War II he joined the RNVR and served in steam gunboats patrolling the channel. During this period he continued to paint and draw in any spare time. He also designed a system of camouflage for Royal Navy ships which drew on the findings of the effects of disruptive colouration (Dazzle painting) used in WWI. His design involved camouflaging ships in pale colours to avoid detection at night and was used extensively by the navy. After WWII, in response to the decline in bird populations, he founded the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust in 1946 at Slimbridge in Gloucestershire, where he lived and painted for the rest of his life.

His inspiration for painting continued to come from the wildlife he saw. As well as working to exhibitions, he also worked on commissions, producing two or three paintings for clients to choose from. His work was almost all done from memory but occasionally it involved making rough sketches beforehand and using aids such as field sketches and photographs. Often when painting birds against a sky, he would put the sky on first and the birds afterwards when the sky was dry. In his early paintings, the brushwork is free and energetic and this is less so in his paintings after the war, perhaps because he spent more time doing detailed illustration. During one period, he used his wife’s cast off tights to create a stippled background effect onto which he painted landscapes with flying birds. At various times in his life, he concentrated on composite paintings with a message. His most famous painting of this kind is ‘The Natural World of Man’, which depicts a person, half white and half black, standing before man’s creations on one side, including a nuclear mushroom cloud, industrial cities, and the human population explosion, and on the other side, the natural world, including endangered species such as the blue whale and whooping cranes. The message is clear – the future of the natural world hangs in the balance.

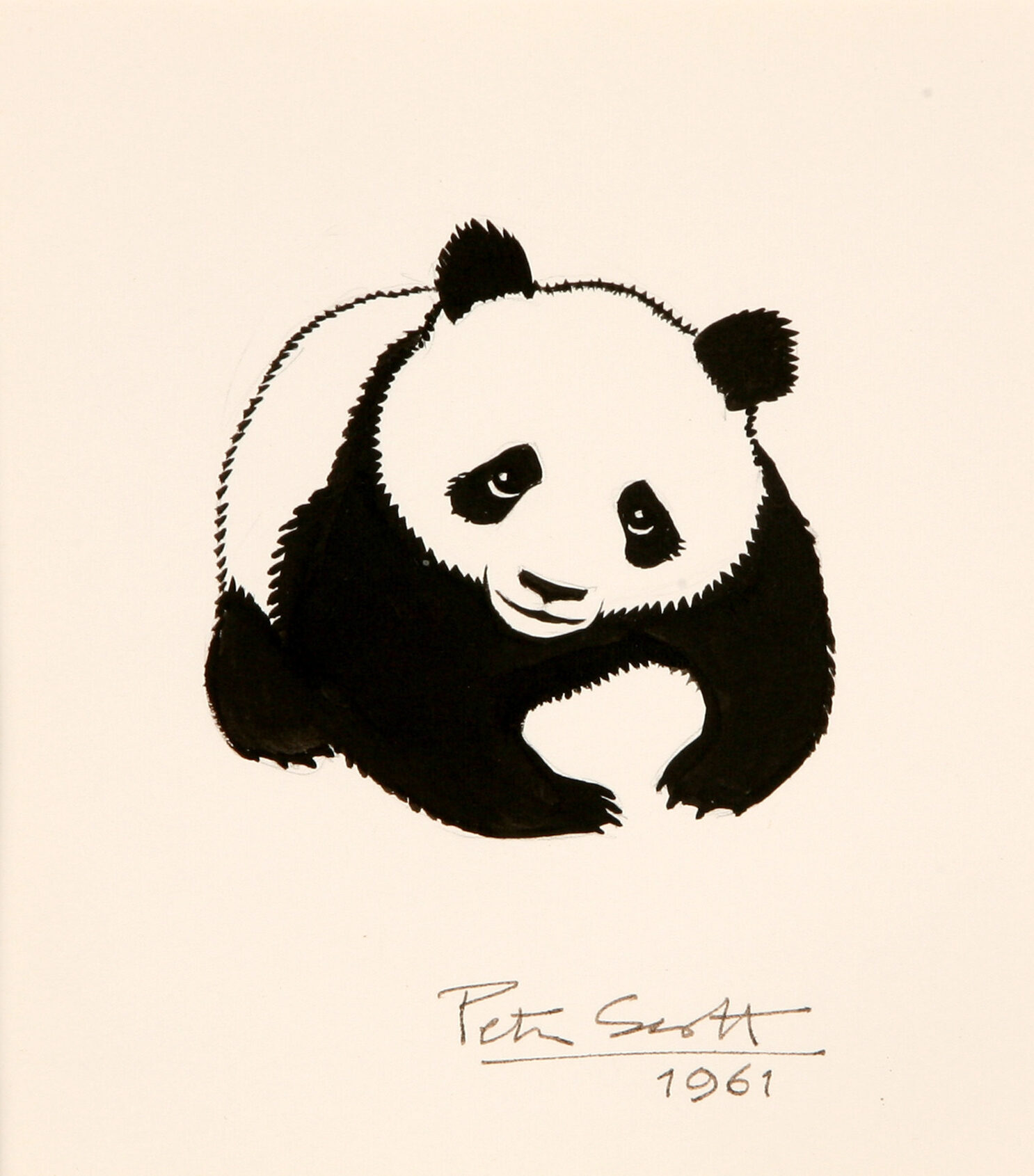

In 1961, responding to the decline in animal populations worldwide, he helped to found WWF and to design its panda logo, and instigated the Red List for the Species Survival Commission (SSC). He was the first person to be knighted for services to conservation and was described by Sir David Attenborough as ‘the father of conservation’. For his contribution to science and conservation, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. He invented and used rocket-netting to mark large numbers of geese, so as to follow the migration of individuals and discover the threats to their survival. He observed the different bill patterns of individual Bewick’s swans and realised that this could be used to study the lives of individuals – a study that continues to this day.

Throughout his life he was involved in a range of activities. In early life he became keen on sailing, winning a bronze medal at the 1936 Olympic Games, and later invented the trapeze enabling racing dinghies to sail faster. Later, when he couldn’t go sailing, he began gliding and became British National Gliding Champion in 1963. He also became interested in scuba diving which enabled him to watch coral reef fish more closely than by snorkelling.

Peter Scott achieved world recognition as a forward looking conservationist, interested in all living wild things, and was among the first to appreciate the importance of conserving the environment as an effective way of conserving wildlife. He worked tirelessly to communicate the importance of wildlife to people at the same time as earning his living as a painter.