Review of The Natural Eye 2012

The Kick Inside: Suggestion, Expression and Loss at The Natural Eye 2012

Bones and Metal. That was what did it for me at this year’s Natural Eye. Bringing together 200 or so works of around 45 exhibiting artists, it was the impervious hardness of the inorganic materials of Harriet Mead’s sculptures and the beautifully emphatic grace of Barry Woodcraft’s Nene that made me want to scratch away the surface and think about what lay beneath.

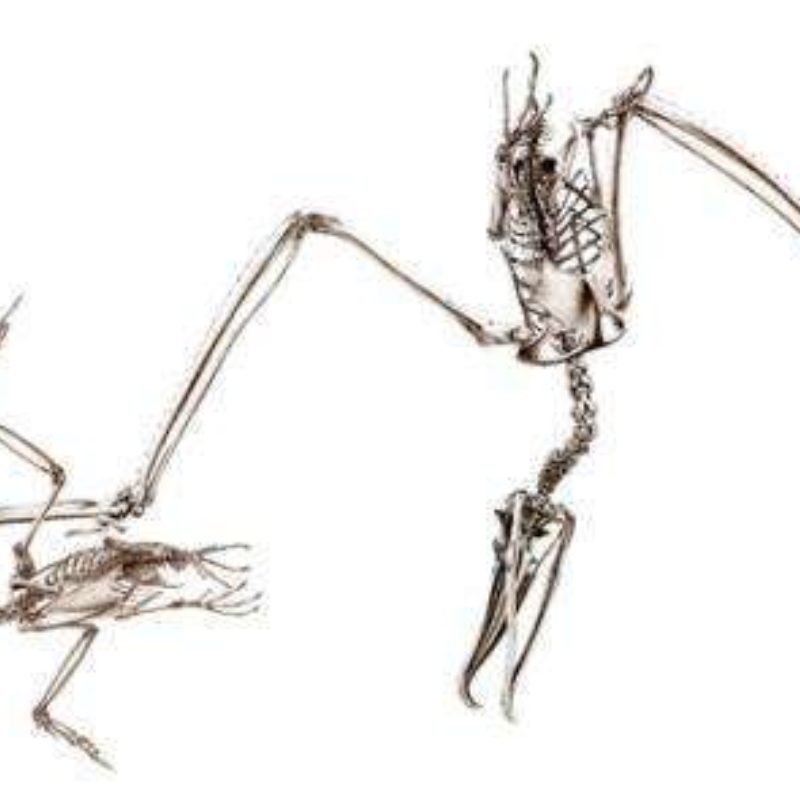

And Katrina van Grouw’s Pursuit and Chris Wallbank’s Signs of life; under the barn eaves delivered just that. In one the skeletons of the birds reveal themselves as what moves beneath the skin. In the other, white on black, those same bones of birds and mammals are reduced to bundles of waste, just as the barn owl’s pellets have left them. And it was that theme – the forces driving the flesh – that the exhibition as a whole shared.

Across every medium there were powerfully taut reminders of this force, its expression and its fragility. Adam Binder’s sculpture Grey Wolf in all its four-wheel-drive glory had every joint dipped in glistening oil, shouting and screaming the musculature. And from the most detailed expressions of what’s under the skin to the scantest expressions of the living, breathing animal the best, most striking of the images of the exhibition were where the subjects were mere suggestions of themselves.

These were broken down and reconstructed into their most vital colours (or even no colour at all), their most basic shapes and reduced to their most crucial angles. As I was working my way through the exhibition I overheard a man who had paused in from of Rachel Lockwood’s Resting Hares – one of the most abstracted images, (where the hares are just a palimpsest of themselves in the landscape) saying to his companion “that really IS a hare, isn’t it.”

It was these works, where the subjects are lightning-quick assimilations of colour, shape and form that were the most resonant and recognisable; the flashing images that most resemble our experiences with each of the animals.

For example, Darren Rees, while not allowing us to see the whole animal, produced a palpable expression of size, grace, colour and being in his Whaleshark and Fusiliers. Likewise, Esther Tyson’s A Personal Sense of Place series not only prompted me to think about the context of familiar birds given the titles of the seven paintings but also allowed the eye only the briefest glimpse of form in order to drive home what it is we’re looking at. Talking of which, the study by Frederico Gemma, Red Deer herd running shows the animals running away. That’s what I’d expect, that’s what they did because rounding the corner of the frame I took them by surprise.

Animals caught as we would find them at any given moment is, of course, always the aim of the artist. Quite powerfully, many works seemed allied to the beginning and end of the day, just as full light is lost or not quite with us. Last light, Silverdale shows the silhouetted Egret of Fiona Clucas caught in the tidal creek exactly as we would expect to see it and in the extremely recognisable work of Brin Edwards such as Summer Dunlin one is under no illusions that the dazzling reflected light is reaching your eye having been pushed through the bird towards you. John Threlfall’s guillemots in Deepening Shadows, St Abbs Head come to us in the evening’s crossing lights and the full backlit glory of Stefan Boensch’s Resting Cormorants leave us bereft of colour but in no doubt about the birds’ reptilian ancestry.

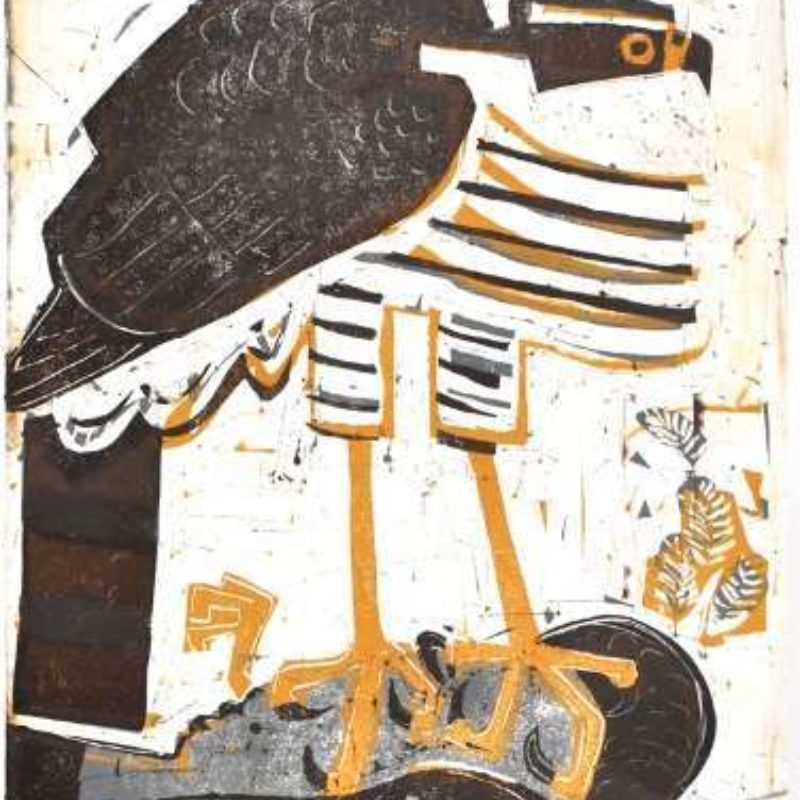

The printmakers represented seemed participants in the same manifestos and this was also the medium in which I most felt the interplay of landscape and subject. Carry Akroyd’s Dark Mere and Max Angus’ Pinkfeet asked difficult questions about whether the landscape is something upon which we impose our experience or whether we allow it to shape our perception. In this context, close views of the subjects, or even a realistic impression, are not necessary to understand them.

The fleeting but visceral nature of the work (and therefore the subjects themselves) was exposed further in Out of the Frame, allowing visitors a glimpse of the notebooks of artists. It’s here that we see drawings made with brutal economy: frigate birds, penguins, landscapes and whales in two or three pencil strokes. Moreover, in exploring active conservation and loss through the eyes of Esther Tyson and Dafila Scott particularly, the very faintness and impermanence of the sketches and quickly drawn portraits provide a reminder of just how quickly habitats and species are dying in front of us. The urgency of the situation reflected clearly in the quickness of the execution.

Out of the Frame was also the entry point for the human element of the story behind every work. So frequently our appreciation of the human place in the image is perhaps reduced to how familiar it seems to us or the knowledge that a human artist has executed it. But in Esther Tyson’s work from Nepal, the very human cost of natural loss and the human place in the chain of events was evident in her storyboard sketches of local involvement in vulture conservation: Cultural diversity as directly proportional to natural diversity.

Life beneath the skin, the fleeting immediacy of the life itself and our part in the loss of it. All three ages reflected in the subjects and their execution. Because, finally, it’s Greg Poole’s Sparrowhawk on feral pigeon that for me captures the spirit of this year’s exhibition: “I am here, I see you. And yet you are seeing me for the very first time.” I’d like more time to understand. I’ve never been so disappointed to see a red dot.

Colin Williams is a writer, naturalist and wildlife tour guide. He has been working in and around the natural world for over a decade and has had work internationally published. He has most recently worked as Writer-in-Residence at WhaleFest 2012.