Ibby Lanfear - The Natural Eye Bursary Winner 2021 Report

The project has also encouraged me to explore other, more abstract avenues for my work, as well as increasing my understanding of the development of early script, and its origins in the natural world.

Ibby Lanfear

I had been aware of the barn owl for some time, and was fascinated by her life, in a secluded barn in a fold of the hills on an organic farm in Devon. Winning the Natural Eye Bursary from the Society of Wildlife Artists gave me the opportunity to develop and spend a year completing a project that has changed both my understanding, and the nature of my practice.

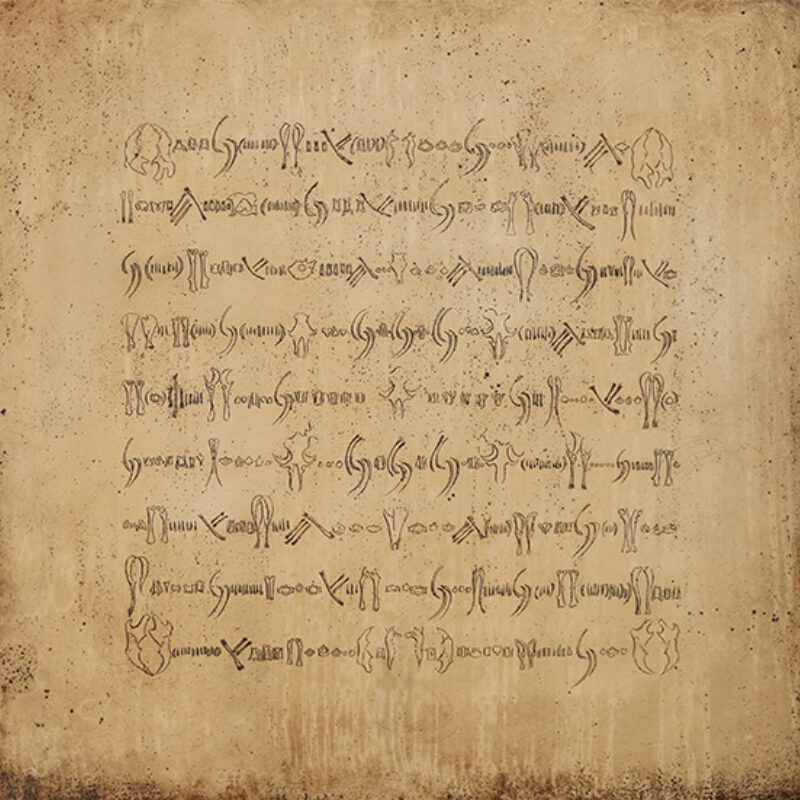

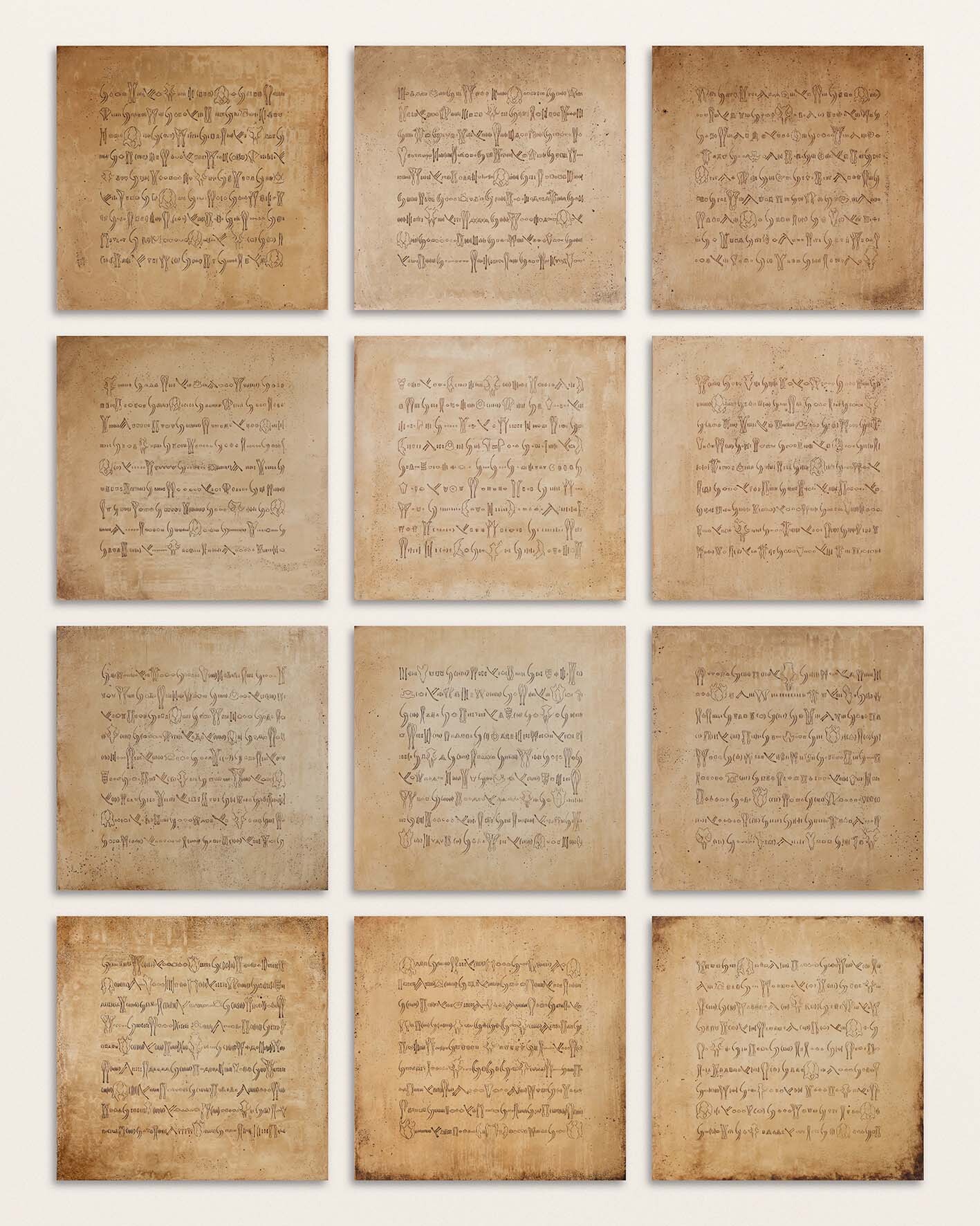

The project aims to tell a story of the owl and the land and life on which she depends through the meticulous recording of individual pellets. It has involved collecting a pellet a month for twelve months, dissecting them and carving the contents on a series of twelve oak panels, which constitute the final piece. In format the work recalls the medieval painting cycles The Labours of the Months. It is an owl calendar. The drawings function as an accurate record of the owl’s diet, and vary significantly from month to month, often depending on her weather-dependent ability to hunt, the availability of small mammals and whether or not she was feeding chicks. In its evocation of early script it is hoped that the work recalls notions of storytelling, and also references the individual languages of the more than human world. In doing so it aims to encourage a consideration of all beings, our collective interdependence through time, with each other, and the environment in which we live.

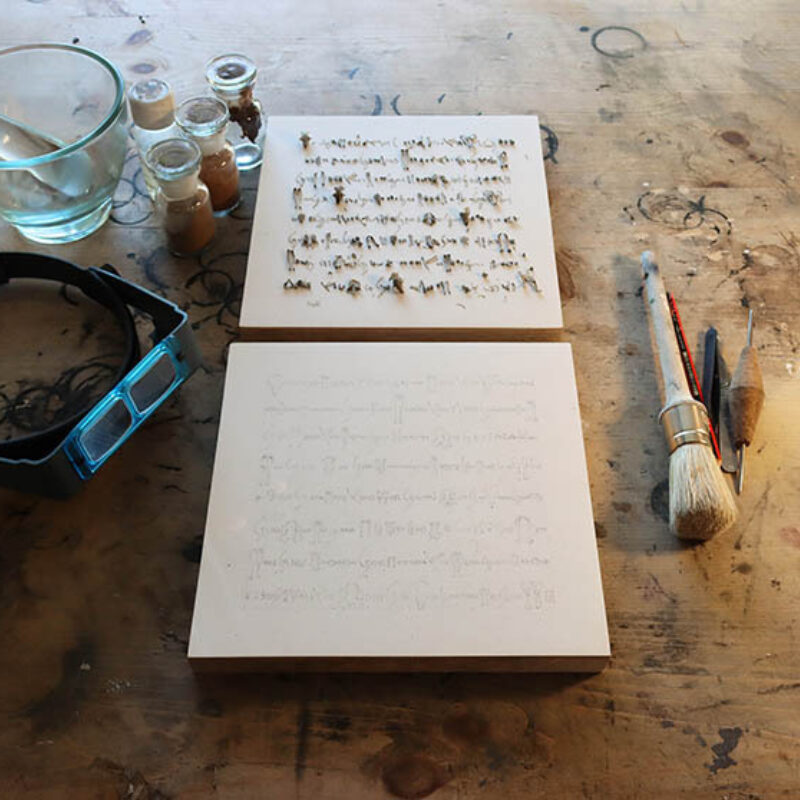

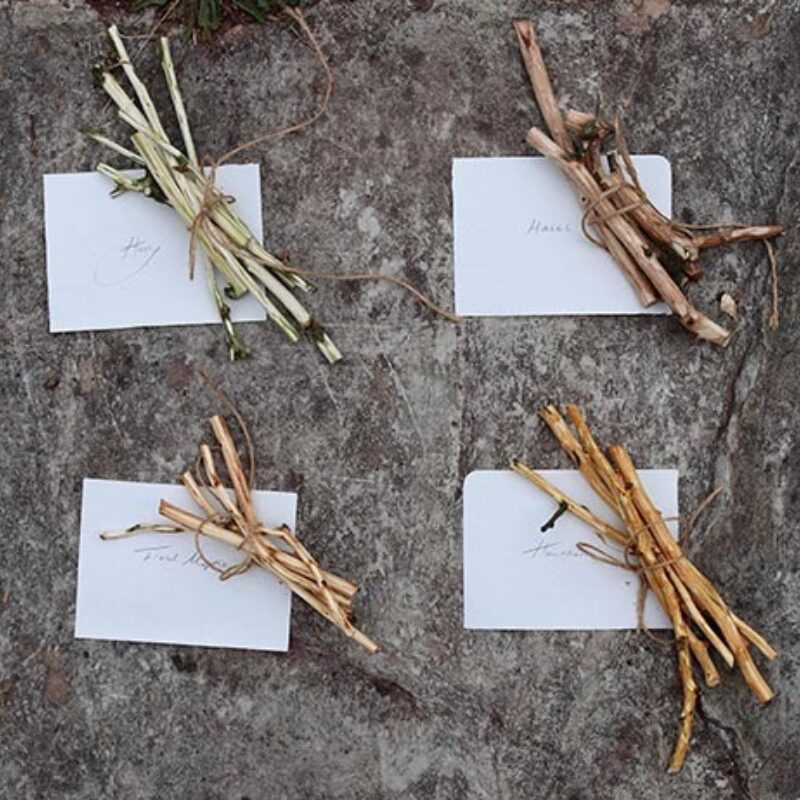

A key element of the project was the creation of the pigments used to make the drawings. The Natural Eye Bursary enabled me to purchase equipment such as a glass muller, a pestle and mortar, and different drying oils. Every month I collected earth from different places within her range, and dead twigs from different trees. I made pigments from the soil, and charcoal from the twigs. Having ground them to powder, I mixed them with walnut oil, and used this to stain the panels and the carvings of the pellets. Taking the owl’s barn as a central point, I developed an intimate understanding of the different areas that she hunts. The final panels, with their time and site-specific pigments, have also become a physical record of her world, the nature of the changing landscape itself, and the other beings on whom she is dependent for life.

Whilst the work is representative in its depiction of many hundreds of bones, the project has also encouraged me to explore other, more abstract avenues for my work, as well as increasing my understanding of the development of early script, and its origins in the natural world. I hope to be able to take this knowledge forward in future projects.

Winning the Natural Eye Bursary allowed this project to become a reality, and has also encouraged local interest, and increased understanding of the life of this owl, and other barn owls in the area, as well as the threats they face. Now the year’s study is complete, and I have spare barn owl pellets, I am looking forward to holding a workshop for their dissection with local children who have shown great enthusiasm for the project.

Over the course of the year, I have spent many, many hours tucked amongst the brambles, watching the barn and the comings and goings of a truly remarkable fellow creature. I will miss her, and am incredibly grateful to the Society of Wildlife Artists for giving me the opportunity for this insight, and for enabling me to develop my understanding and my practice in ways which would not have been possible without the Natural Eye Bursary.